The healthcare system at large has experienced a notable increase in the share of providers and health systems assuming financial risk for the total cost of care. The rise of these value-based models has historically been driven by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), with programs focused on populations of high cost and cost variability—specifically, those aged 65-plus with chronic conditions. However, over time, state Medicaid programs and commercial payers have begun introducing value-based contracts of their own, including those focused on high-risk children.

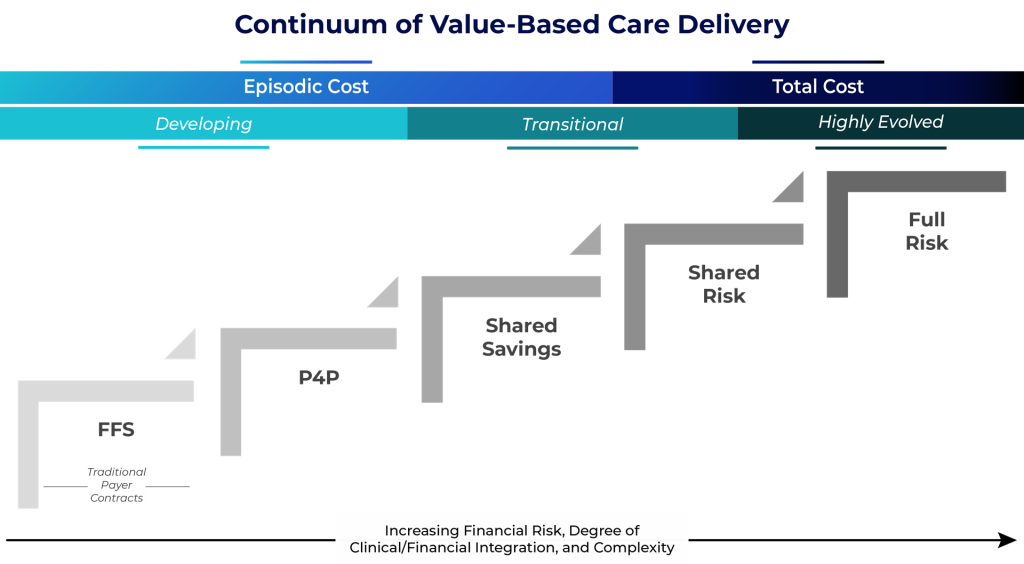

The term “value-based care” encompasses a broad continuum of care delivery models, and each requires a different degree of financial risk assumption, as depicted in figure 1.

- Low-risk models include those that focus on episodic costs, such as pay-for-performance (P4P) and shared savings. These structures offer an opportunity for providers to earn financial bonuses based on quality performance without any downside risk.

- More evolved value arrangements may follow a shared-risk or full-risk structure, in which providers have a greater potential for financial upside, but in return, must also assume downside risk in the event healthcare spending exceeds a predetermined amount or quality thresholds are not met.

Figure 1

Within pediatric institutions, a majority of existing risk programs are based on episodic costs and include limited, or no, downside financial risk. However, given that most nationally recognized children’s health systems have either clinically or financially integrated physician organizations, they are able to coordinate care effectively and succeed under pay-for-performance or shared savings arrangement types. Only a select few pediatric systems have progressed across the value continuum to assume full financial risk for a defined population (these include Texas Children’s Hospital and Cook Children’s Health Care System, both of which formed their own health plans).

Unique Challenges Result in a Gradual Adoption of Value

Pediatric organizations have been slower to adopt shared- and full-risk models for a variety of reasons, including:

- Metrics that appropriately and accurately measure pediatric outcomes and quality of care are limited. Where these metrics are available, they are often difficult for payers to implement and operationalize when compared to traditional, adult-focused metrics.

- Patients treated in these pediatric systems are often high-acuity, complex cases. This poses challenges for traditional value models, which are often centered on primary care providers.

- A lack of adequate pediatric post-acute care providers makes it difficult for systems to coordinate and manage care beyond the acute care setting.

- Once a program is developed, pediatric systems may have difficulty developing a reliable methodology to assess and stratify their pediatric population by risk profile—a key component for success under a total risk arrangement.

- Operationally, pediatric systems may lack fully integrated electronic health records that can share data across a broader network of independent specialists and providers.

These compounding challenges have led many pediatric health systems and payers to conclude that global risk assumption, as it is currently presented, is not transferable to the pediatric population.

That said, most pediatric organizations are already investing in capabilities such as advanced care management, care-at-home models, and digital health. However, many of these organizations have developed this infrastructure out of necessity to improve operations, support patient throughput, and free up inpatient capacity. In other words, they’re delivering value for payers but aren’t being reimbursed or recognized for their services.

Therefore, pediatric systems should first focus on aligning current reimbursement terms to account for any support services they are providing that may not be directly reimbursable under traditional fee-for-service contracts. This may include care management or coordination services through strong inpatient and affiliated outpatient networks, or virtual follow-up and e-consult programs used to reduce readmissions. To support their case, pediatric systems will need to quantify how these efforts reduce costs, create additional capacity, resolve access constraints, reduce utilization, and reduce readmissions. Based on these generated savings, the organization must be prepared to approach payer partners and propose a payment structure that will ensure compensation for value-added services.

Pediatric Systems Should Proactively Assess Value Readiness

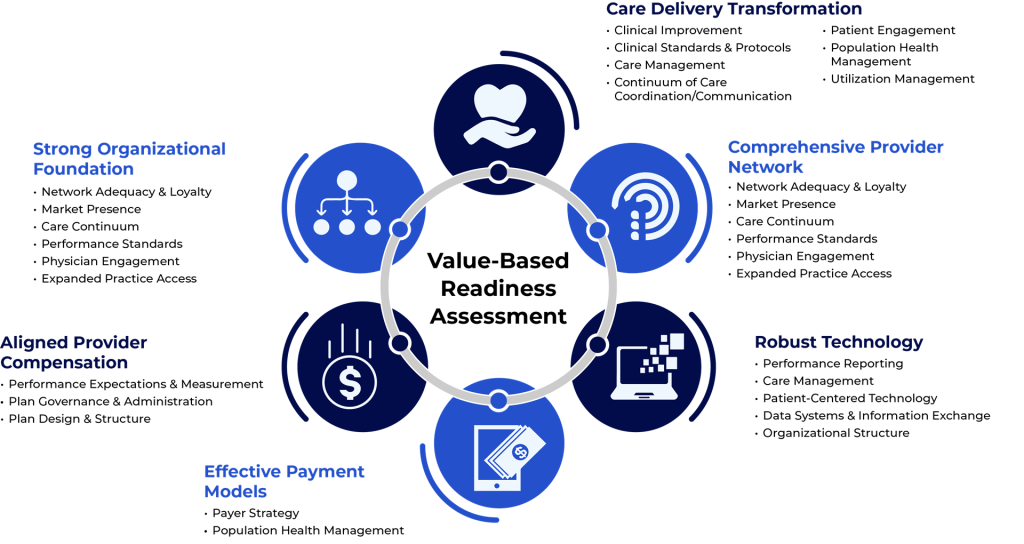

For pediatric organizations that are prepared to move to the next phase of risk assumption, leadership will first need to conduct an assessment to determine the degree of organizational readiness. For instance, ECG evaluates value-based readiness on a set of key criteria, as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2

While full-risk models may not be immediately viable for most organizations, pediatric systems need to proactively evaluate their readiness to assume financial risk and then develop a strategy that aligns reimbursement with organizational goals, clinical and/or operational investments, and projected market pressures. ECG expects the uptake of risk in pediatric care to be gradual, but we also anticipate that trends such as rising patient acuity, demand for integrated behavioral health services, and the growing focus on early intervention will continue to push the conversation forward.

If approached correctly and with adequate preparation, value-based care can offer pediatric systems a unique opportunity to enhance quality and outcomes for their highest-risk patients while generating incremental revenue and positioning their organization for long-term success.

Edited by: Matt Maslin