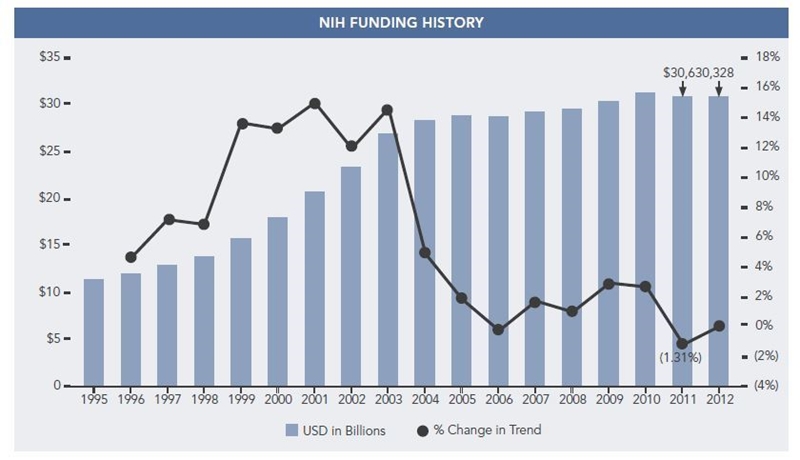

The NIH budget is proposed to stay at FY 2012 funding levels, or $30.7 billion, per President Barack Obama’s FY 2013 budget proposal released on February 13, 2012.1 In a quick review of NIH budget trends, the slow growth from 2000 to 2011 is very apparent,2 with the only significant reduction in 2011 being 1.3 percent. Looking forward, research and development (R&D) funding is highly likely to decrease as part of an effort to reduce the federal budget, especially given the recent Congressional Budget Office’s report, The Budget and Economic Outlook: Fiscal Years 2012 to 2022.3

Anticipated funding reductions will require a focus on cost-effective research operations. Other major trends that research institutions need to be aware of involve new content areas and processes. CER, translational science, and implementation science have both funding and policy driving more resources and attention. Processes will need to be updated to improve our ability to measure outcomes, engage patients, and understand changes in operations as the healthcare research industry continues to evolve.

This article provides a summary of federal research funding key considerations, both planned and expected, in the next 5 years.

Currently, the only legislation in place impacting future budgets is part of the federal deficit deal (Budget Control Act of 2011) that outlines automatic reduction triggers starting in 2013 as a result of a failure of the Congressional Super Committee to reach a deficit deal. Reductions include discretionary and non-defense spending, which would impact the NIH and other R&D organizations, including the National Science Foundation (NSF).4 Reductions start at 7.8% in 2013. If the amendment remains in place, we can expect R&D funding to decrease, perhaps significantly over the next 10 years.

A Shift in Focus for Research

One of the biggest indicators of where research at the NIH is headed is symbolized by the launch of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). The center reflects a continued effort to reduce the amount of time and money needed to move new discoveries from bench to clinical application. NCATS is new at the NIH, but the center is composed of several NIH areas already in place. They will become part of this new center in an effort to further consolidate research, reduce barriers to collaborative and translational science, and present a more coordinated approach to discovery. Key NIH departments that will move to NCATS include:

- Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA).

- FDA/NIH Regulatory Science.

- Bridging Interventional Development Gaps.

- Components of the Molecular Libraries.

NCATS funding moves the budget for these programs to the new center, with additional funding from a few other areas, such as the National Center for Research Resources, which was dissolved with the establishment of NCATS. The total budget for FY 2012 is $575 million.5 For more information on NCATS, now the 27th of the NIH’s Institutes, Centers & Offices, visit the NCATS Web site at http://ncats.nih.gov. NCATS reflects a shift in funding trends toward translational science.

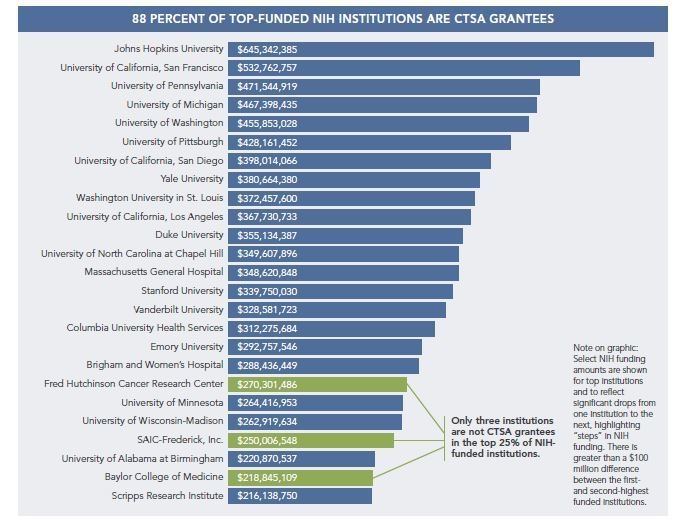

Top-funded NIH institutions are fairly consistently CTSA grantees. Of the top 25 funded NIH institutions, 88 percent are part of the National CTSA Collaboration,6 making a strong correlation with translational science and NIH funding. As noted above, continued focus on translational science will increase, as reflected by the formation of NCATS and the transition of CTSA into this new center.

For those institutions that have yet to secure a CTSA grant, renewed focus to restructure core services and streamline operations to enhance translational science may help position your institution for longer-term success.

CER is the other major shift in research for the foreseeable future. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) is launching this year under its new name and new leadership. Funding for PCORI is achieved through initial federal allocations ($10 million in 2010, $50 million in 2011, and $150 million in 2012). PCORI funding is eventually sustained through a $2 per Medicare member annual fee and $2 per commercial payer member annual fee, reaching almost $650 million annually by 2014.7

PCORI is establishing research priorities and finalizing advisory members and has appointed a new Director, Joe V. Selby, M.D., M.P.H. In a recent interview, he emphasized the goals of conducting research that is meaningful and useful to patients and which leverages knowledge and databases already in place.8 Some work has been done to inform PCORI on what research priorities should be pursued, including a study by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) that was mandated as part of PPACA legislation and identified 100 priorities.9 PCORI is currently seeking feedback that includes any academic institution, provider, patient, or other organization with some thoughtful requests. You can provide input at http://www.pcori.org/.

While research priorities are being developed, we can still prepare for likely areas of emphasis. It is anticipated that these will include at least the following (using IOM’s top 5 categories out of 29):

- Healthcare Delivery Systems.

- Racial and Ethnic Disparities.

- Cardiovascular and Peripheral Vascular Disease.

- Geriatrics.

- Functional Limitations and Disabilities.

Study design and methodology may also need to be addressed in academic research institutions. Certainly, new methodologies must be developed and incorporated into current processes. Policies will likely need to be updated. Most importantly, the focus on

the patient’s perspective should be incorporated into CER studies.

CER is in place in some areas,10 but the funding mechanism and focus has not been structured in such a way that creates a cohesive and focused approach for academic research institutions, nor have we had access to information from the patients’ perspective and behavior outside of traditional care delivery settings (clinics and hospitals). As an industry, the technology infrastructure and analytic capabilities are not where they need to be to operationalize a robust infrastructure and easily capture this information. Nonetheless, the transition is starting. New mobile devices, remote monitoring capabilities, and user-friendly interfaces continue to surface, making this information accessible.

Positioning the Research Enterprise for Success

Looking forward, the themes seem familiar in terms of the national conversation of the U.S. economy in general: pursue cost reduction and improve efficiency and effectiveness. In addition to these themes, research institutions will also need to direct some energy toward translational medicine and CER. Academic institutions can improve their position by:

- Reducing Research Operating Costs.

- Enhancing Translational Science.

- Creating CER Capabilities.

- Establishing Implementation Science.

- Developing Collaborations and Partnerships.

- Leveraging Technology Innovation.

- Framing Research in Terms of Economic Development and Contribution.

- Funding the Academic Mission – Implications.

Reducing Research Operating Costs

Improving operations efficiency in the research setting can be challenging, especially when many labs operate independently of each other. Improvement in operations efficiency and cost reduction can be accomplished through the following:

- Identify core services that can be shared and restructure them to improve access, response time, and cost of operations.

- Review research program governance such that the financial and operating performance of the enterprise is reported, and managed, as a system.

- Consider competitive bids for services used across many labs that might be more efficiently run by capable business partners.

- With facility redesign, help improve access, with core services collocated near the labs that use the services the most.

Enhancing Translational Science

Translational science will continue to be emphasized by federal and private research sponsors, if only to improve the efficiency of investments in research. More academic institutions will find an increasingly competitive environment for fewer available funds. It is unlikely that federal funding will increase significantly over the next decade while there is a need to address the federal deficit. Private industries are also looking for the most cost-effective outcomes of their research investments – internally and externally.

Those with successful CTSA bids understand how much reorganization of the research enterprise is required to enhance translational science. For those with unsuccessful bids, perhaps they appreciate the challenge even more. Yet, NIH funding trends can be an indicator of which institutions are likely to secure more funds in the future, despite any changes the NIH might make to award more first-time applicants. CTSA requirements can serve as a good guide regarding what is needed to enhance translational science. Even if you are no longer pursuing a CTSA grant, you might continue to implement the kind of operational restructuring, core services, and cross-department collaborations inherent in that model.

In general, the more we can improve research efficiency in a manner that benefits patients, the more successful the research enterprise will be.

Creating CER Capabilities

CER is under development in many ways and is not yet a major part of most research programs. Creating the capability to pursue CER research will require new investments in informatics, patient engagement, epidemiology, population health, and implementation science. Much of what CER requires is consistent with the changes in provider and patient-centered care delivery that PPACA is shaping through CMMI and other avenues. Investments made in informatics will serve both CER and changes in patient care that improve care coordination and track performance against a set of outcomes measures.

Creating CER capabilities includes the following:

- Invest in informatics that can integrate clinical, research, and financial data. Informatics solutions will be important in capturing patient input through portals, mobile devices, and personal health records to understand effectiveness outside of the traditional patient care delivery setting.

- Leverage the academic expertise in population health, epidemiology, health economics, and other areas that assist in understanding your patient demographics in ways that can create system research and clinical priorities.

- Develop the policies and procedures in your research institution to incorporate effectiveness of treatment, education, and interventions.

- Establish patient engagement efforts that can span the clinical and research operations, creating a relationship that will track effectiveness with patient input. Consider ways to solicit patient advice on study design, interventions, and outcomes in a manner that patients would deem effective.

- Continue to consolidate research resources and capabilities and collaborate across departments, institutes, and centers – internally and externally – which leverages resources and improves the information available on care effectiveness.

Establishing Implementation Science

Implementation science is an ideal segue from translational science to CER, and it can provide ongoing evaluation/improvement for CER. Implementation science can help inform policy and operations. There are implications for patients, healthcare providers, payers, physicians, and policy makers.

Implementation science is not new, but it has not had the focused structure and priority of other areas of research.

As CER reveals more effective healthcare interventions, provider institutions will need ways to translate those findings into practice. Implementation science is the research and methodology that will be instrumental in improving the effectiveness of research and medicine. Areas of focus in implementation science include adoption practices, guideline effectiveness, system processes/operations, patient/population behavior, etc.

Operations research, implementation science, operational effectiveness – these terms are related to the core area of improving operations, which translates to effectiveness through practice. As cost pressures and the need to engage patients more in their own health and wellness drive change, implementation science will become a more significant area of study. The need to establish a focused framework, processes, and pursuit of efforts around implementation science will be important for leading academic institutions.

Developing Collaborations and Partnerships

Collaborations, partnerships, sharing of infrastructure, diversification of the research portfolio – all of these ideas must be explored. In addition, online collaborations and other technology can be leveraged to cost-effectively conduct research.

Collaborations and partnerships are already encouraged by the NIH, as modeled with the Division of Program Coordination, Planning, and Strategic Initiatives (DPCPSI),11 which is part of the NIH. A few highlights of collaborations include the following:

- CTSA – This is a major NIH initiative to streamline research institutions (internally and across disciplines) so as to shorten the research cycle, thereby increasing translational science and improving research efficiency. The earliest awards were issued in 2006 to a select few institutions. There are currently 60 participating institutions. Of these, many are the NIH’s top-funded institutions and leaders in research discovery.

- Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network (CPCCRN) – This covers the study of several topics in the pediatric critical care environment. The University of Utah serves as the coordinating center and plays a critical role in the data management of studies. This is an external collaboration.

- Biomedical Translational Research Information System (BTRIS)12 – This system is an investment by the NIH to improve access to research data. A pilot initiative was completed in 2008, and BTRIS was made available in 2009. BTRIS is still expanding to include data from more institutions. A significant investment in data governance was made such that BTRIS could scale many data types and access to research databases/information. As budget reductions become imminent, BTRIS may become more attractive as a data source for participating institutions to secure research funding, while also being able to share some of the infrastructure already developed for this purpose. BTRIS’ greatest value is as a faster path to findings, based on access to a broader set of shared data.

The NIH provides a detailed report of the trans-NIH collaborations, highlighting work across 24 of the 27 NIH’s Institutes, Centers & Offices.13

The private sector has also led in developing partnerships and collaborations as its business model has been challenged, requiring it to seek more efficient approaches to R&D. The M2Gen14 collaboration between the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute and Merck & Co., where Merck develops personalized molecular cancer treatments for patients, is an example of the kinds of partnerships that are needed. Partnerships like these are much more common and will continue to develop as the business environment allows. Pharmaceuticals have shed components of their R&D business that escalated during the recession, partly in response to an anticipated significant loss of patents in the next year.15 Academic institutions have wanted to become less dependent on government funding for research and welcomed partnerships with pharmaceutical and other companies. Pharmaceutical companies are refining their focus, hoping academics will pick up much of the early-stage drug discovery R&D. Cost pressures on all sides are the drivers. Partnerships are necessary for all involved. There are implications for indirect expenses, as indirect funding from private industry is generally much less than federally sponsored research.

Leveraging Technology Innovation

Technology innovation is changing the way that research is being conducted in that it allows for online collaboration outside of the traditional grant-supported study model. A recent book, Reinventing Discovery: The New Era of Networked Science,16 highlights these changes. Scientists are collaborating together to help solve problems or hurdles that develop during the discovery process. These trends are worth taking note of in that they challenge our current model of research and its inherent peer-reviewed processes. This new approach can incorporate peer review. Online collaboration may take a while to impact the research enterprise, but in the interim it may feel like a creative destruction process where funding is not currently tied to this new model. If successful, we may see a shift in the business model of research. This has the potential to be more cost-effective. More importantly, this kind of model can contribute to reducing time from discovery to application.

Private industry has made changes to decrease the costs of R&D recently, even as the pharmaceutical industry prepares for the loss in exclusivity of 110 products from 2012 to 2014.17 Private spending has increased on pharmaceutical development, yet the emphasis in the private market has changed to higher-impact drug development activities. In the past 5 years, many pharmaceutical companies have downsized their early-stage drug development R&D operations in hopes that they can partner with smaller firms and academic institutions to conduct components of drug discovery that had previously been done internally. This has led to both interest and challenges for AMCs. There is an interest in diversifying research funding sources such that private industry plays a role, while balancing the development costs of early-stage drugs and other research activity. Private research partners require academic institutions to improve processes and policies that enhance intellectual property in a manner that aligns interests with private industry and academia, while also competing for private funding as efficiently as the private industry can.

Technology innovation in research will provide the ability to incorporate patient behavior and perspectives into science to enable CER, outcomes-based research, implementation science, and other areas. As an industry only a few institutions today are incorporating data from patients directly outside of traditional care delivery settings or from in-patient visits (either through remote monitoring devices, patient health records, or other ways to incorporate patient behavior and feedback directly to a provider-sponsored/-managed health record system). As systems allow more ways for patient input, information available for research will broaden. It is this next horizon of technology and ease of patient input that can be incorporated into research knowledge.

Framing Research in Terms of Economic Development and Contribution

At the 2011 AAMC Annual Meeting, Francis J. Collins, M.D., Ph.D., Director of the NIH, noted that changes are likely in the NIH funding portfolio as part of how the NIH will respond to budget reductions. He also mentioned the need to highlight the economic contributions that research makes. At the same meeting, a study conducted by Tripp Umbach showed that research contributed $45 billion to the U.S. economy in 2009 and supported 1 in 500 jobs.18 While Dr. Collins noted that he never thought we would need to quantify research in economic contribution terms, he emphasized the increased importance of doing just that in order to protect funding as the U.S. continues to struggle to emerge from the recession.

Many local communities have developed economic development organizations, some in response to the recession. Whether your community has such an organization or not, there is likely an interest in sharing the jobs created by the academic and research activity that you pursue. Spending time framing your research activities in that context could be very beneficial. Valuing research and the academic mission for academic institutions will be more imperative, especially as we move away from our traditional reimbursement and funds flow models. If additional support is needed, your business community should be fully aware of how that support affects the local community in a positive way.

Funding the Academic Mission – Implications

New partnerships with more commercial research funders require AMCs to sharpen their intellectual property regulations and processes, while also preparing for decreased funding of indirect expenses. The federal government funds indirect expenses at an average of

40 percent; private industry often funds indirect expenses at less than half of that rate. The higher the percentage of private research sponsors, the more efficient research operations will need to be as indirect expense support declines.

Looking forward, we anticipate stagnant, perhaps even declining, federal research funds. The Congressional Budget Office issued a series of projections in its economic outlook report for 2012 to 2022,19 identifying one scenario where Social Security and major federal healthcare programs increase to 12.8 percent of the U.S. gross domestic product by 2022.

The report highlights the continued escalation in healthcare costs, which is creating a platform for needed change. Declining funds will likely be part of how a growing federal deficit is addressed.

Conclusion

The role that research plays in our healthcare system cannot be overemphasized. Discovery, the improvement of patients’ lives, and the general health of our population are paramount to our collective interests in research. At the same time, R&D in healthcare is facing unprecedented challenges. Our traditional models of pursuing, conducting, and delivering research need to evolve so that R&D efforts can be sustained, grow, and improve the impact on patients’ lives.

Our industry’s challenge is to evolve research in a way that leverages new technology and models and incorporates a broader perspective in a more cost-effective manner. As we move toward CER, and include patient input as early in the process as study design, the need for all current areas of emphasis will be challenged. Basic science, discovery, and funding will be particularly challenged. Savvy institutions will construct a framework for these areas that aligns them with the new direction of research and funding.

We believe that there is a path to transition to even more effective research enterprises, as we have outlined in this Insight. Certainly, we will all learn from the journey that lies ahead.

Footnotes

- http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/….

- http://officeofbudget.od.nih.gov/spending_hist.htm….

- http://cbo.gov/doc.cfm?index=12699.

- http://www.ombwatch.org/files/budget/debtceilingfa….

- http://www.nih.gov/about/director/ncats/faqs.htm.

- 2011 NIH institution funding includes R&D funds: http://www.brimr.org; CTSA institutions: https://www.ctsacentral.org/ctsa-institutions. Note that Massachusetts General Hospital, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Massachusetts Institute of Technology are all part of Harvard Catalyst.

- Legislation establishing PCORI, as part of PPACA: http://www.pcori.org/assets/PCORI_EstablishingLeg…..

- Susan Dentzer, “The Researcher-In-Chief At The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute,” Health Affairs, Vol. 30, No. 12, December 2011, pp. 2252–2258.

- http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2009/ComparativeEffecti….

- For a discussion on current CER activity, both federal and commercial, see http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2009/ComparativeEffecti…, pp. 46–53.

- http://dpcpsi.nih.gov/collaboration/committees.asp….

- http://btris.nih.gov.

- http://dpcpsi.nih.gov/pdf/2010_Report_of_Trans-NIH….

- http://www.m2gen.com/pages/index.cfm.

- http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/07/business/07drug…..

- Reinventing Discovery: The New Era of Networked Science, Michael Nielsen, Princeton Press, 2012.

- http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/06/26/pharmace…

- https://www.aamc.org/download/265994/data/tripp-um….

- Congressional Budget Office, The Budget and Economic Outlook: Fiscal Years 2012 to 2022, Presentation to the National Economists Club, Douglas Elmendorf, Director, February 9, 2012, http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/127xx/doc12752/NEC_2-9-….