Patient complexity is one of the biggest factors reshaping the health care industry, but it’s not top of mind for most hospitals. That’s going to change rapidly as value-based principles and capitated models take hold, incentivizing hospitals to limit inappropriate health care utilization.

Kurt Salmon expects 20% to 30% of all basic non-maternity inpatient care to transition out of hospitals and into ambulatory settings in the next five to ten years. Meanwhile, hospitals will devote an ever-increasing share of beds to caring for patients at either end of the complexity continuum—necessitating changes to how resources are allocated, with investments in intensive care and observation platforms coming at the expense of general acute care capacity.

Basic-complexity patients will shift out of the hospital for multiple reasons: Some who never should have been admitted in the first place will have new alternatives as care models evolve; others will be transitioned to lower-cost settings as monitoring and treatment technologies evolve and reimbursement focuses less on volume.

Currently, hospital facilities aren’t set up to cost-effectively treat basic-complexity patients, who typically use fewer resources and have shorter lengths of stay. But they are starting to explore alternative, lower-cost approaches as they transition to population health strategies and take on greater reimbursement risk. The shift has already begun, particularly for select surgical procedures in specialties like gynecology, ophthalmology and urology. More will follow.

Complexity 101

To determine which services are ripe for transitioning out of the hospital setting, providers must have a complete picture of their current patient complexity. Yet in defining patient complexity, many hospitals rely solely on the case mix index associated with the Medicare Severity.–.Diagnosis Related Groups. While a valuable metric on its own, using the case mix index in combination with four other factors—patient age, admission source, charges and length of stay—provides a more holistic, nuanced picture. (See Exhibit 1.)

Using these criteria, hospitals can segment patients into three broad complexity-based buckets—high, moderate and basic:

- High-complexity patients are spread across select service lines (like neonatology, neurology, cardiac, cancer and transplant) and often require multidisciplinary care. As a result, they are often resource intensive, requiring highly specialized staff, ICUs, large ORs, and MRI or PET/CT scanners.

- Moderate-complexity patients represent a large portion of a hospital’s elective volume and historically have commanded a higher commercial pay percentage. They typically require a large outpatient clinic base, lots of imaging and procedure space, and high-end amenities.

- Basic-complexity patients often drive emergency room use. These patients typically use low-end imaging and have short lengths of stay.

Armed with a more holistic picture of their patient complexity, hospitals can consider how best to care for their patients in the most appropriate cost setting and determine which patients can shift from an inpatient to an ambulatory setting. This change ultimately results in a more complex inpatient base.

Utilization in Florida: The Anomaly That Heralds a National Trend

Six years of inpatient discharge data from every acute care hospital in Florida—over 200 in all, with 50,000-plus licensed beds—shows these complexity shifts in action and offers a snapshot of the changes other states may face as their own populations age.

From 2007 to 2013, total discharges in Florida increased by approximately 115,000. Moderate-complexity and basic-complexity discharges accounted for 22% and 5% of this growth, respectively. High-complexity discharges, on the other hand, accounted for about 73% of overall discharge growth. (See Exhibit 2.) If we look at this on a patient-day (instead of a patient-discharge) basis, high-complexity admissions represented more than 95% of all incremental patient days over that six-year time frame.

This growth in high-complexity discharges in Florida suggests that, regardless of state, the inpatient patient base will continue to become increasingly complex and that the traditional patient mix will look very different in the coming years.

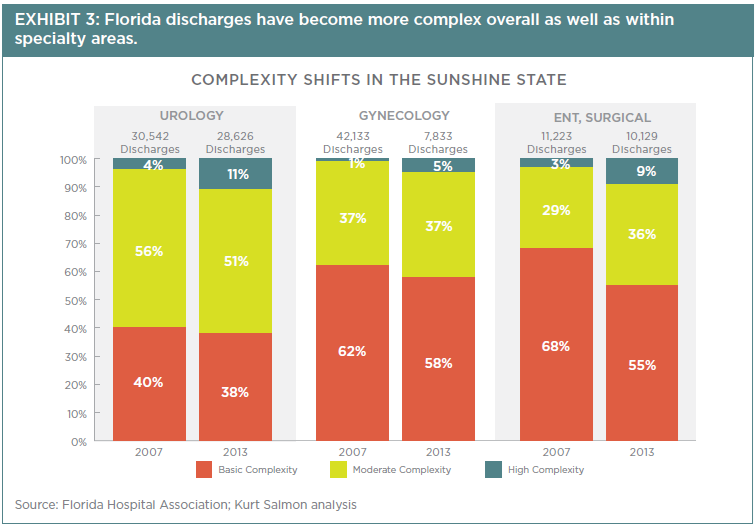

The growth in high-complexity discharges also fueled a change in the overall patient complexity mix. The resultant smaller percentage of basic- and moderate-complexity patients, as illustrated in Exhibit 3, highlights the changes certain specialties have experienced in complexity mix and reduced volume as services have shifted out of the hospital to ambulatory settings.

Further, length of stay continues to trend downward for all patient types, and high-complexity patients drive a larger portion of patient days compared to the percentage of discharges they represent. For example, in 2013, high-complexity discharges accounted for approximately 9% of Florida discharges but 28% of patient days.ii As the segment of basic-complexity patients continues to decrease, a greater portion of patient days will be related to high-complexity care, reinforcing the need for a different mix of resources for the inpatient care delivery platform of the future.

Florida, although grayer than the rest of the country, is a microcosm of a larger national trend: Across the country, utilization will continue to trend downward and patient mix will also change as the pressure to shift basic-complexity patients out of the hospital continues to intensify. And as these patients move out, hospitals will need to find different ways to drive revenue.

Hospitals in general are not currently set up to care for the coming wave of high-complexity patients, which requires a different bed mix as well as robust subspecialty support.

But hospitals in general are not currently set up to care for the coming wave of high-complexity patients, which requires a different bed mix (more ICU, less general acute) as well as robust subspecialty support.

While this change comes with significant implications for all hospitals, the average community hospital will feel it more acutely.

Typically, about 50% of a community hospital’s patients are basic complexity. Since we expect that 20% to 30% of these non-maternity basic-complexity patients will no longer be cared for in inpatient settings, while at the same time the remaining patients will be more complex and require more resources, the question becomes: Can the community hospital keep up?

The way in which many community hospitals are currently structured will make caring for this higher-complexity patient base extremely difficult, if not impossible. But the first step in addressing this issue is to understand the full scope of the change that lies ahead. And that starts with hospitals diving into their own complexity data, making sure one of the most vital stats in the industry doesn’t cause them to flatline.