Medical schools are facing an array of pressures, including declining reimbursement for clinical services, tightening state and NIH budgets, rising industry consolidation, and increasing competition. To remain successful, medical schools are looking to new strategies and priorities, such as reducing costs, pursuing greater alignment of basic and clinical science departments (e.g., multidisciplinary centers and institutes), and achieving greater integration of professional and hospital services. In this environment, the availability of information to make decisions and monitor progress is critical. Medical school deans are discovering that the data needed is difficult to obtain.

There are several challenges particular to school of medicine (SOM) environments that hinder the development of a data-driven culture:

- Desired data is often siloed in mission-specific systems that are not interoperable with data from other systems.

- Due to a lack of strong SOM-specific products available in the market, SOM IT environments are typically homegrown and highly customized to meet a school’s unique requirements.

As emerging strategies require accurate, verifiable, and interchangeable data, the diversity of SOM legacy systems and the lack of standards for data in SOM environments is a significant barrier. More recently, however, system sophistication and technological advances give medical schools the opportunity to implement business intelligence (BI) programs that will facilitate accomplishing strategic objectives and remaining competitive.

In this first of three articles, we will define BI and explain how it can be effectively deployed in SOMs. Part 2 will discuss governance structures that can serve as the foundation for establishing a successful BI program, and Part 3 will address the level and type of staffing necessary to support BI in an SOM environment.

What Is Business Intelligence?

BI is a set of processes, tools, and technologies that convert raw data, typically from multiple systems, into meaningful and useful information. This information facilitates strategic, tactical, and operational decision making. While organizations sometimes define BI programs differently, a comprehensive program generally includes warehousing, reporting, analytics, and decision support.

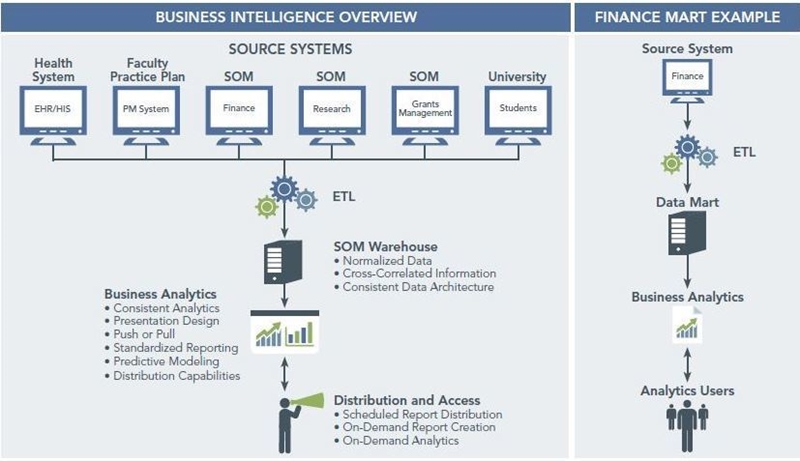

As shown in the graphic below, BI processes involve extracting information from various source systems and transforming and loading it into a consistent database architecture to create a data warehouse. This process is referred to as ETL (Extract, Transform, Load). The ETL process ensures that the information defined in each source system can be mapped to similar information. For example, if a “student” is defined in a university system and then defined differently in an SOM system, the two definitions need to be cross-correlated or mapped so that reporting on students will be consistent. Similarly, if a physician is defined as a “faculty member” in an SOM system but as a “provider” in an EHR, data on that individual needs to be mapped in the warehouse so that his/her activities can be reported between systems.

After data is successfully warehoused, business analytic tools can be used to build reports that slice and dice data in various ways. Business analytics tools vary in sophistication and complexity. Some require programming expertise in order to design reports, while others can be used by anyone within the organization. These tools allow for the manipulation of data to meet the needs of a wide variety of stakeholders. Newer capabilities include predictive modeling, sophisticated graphics, and the ability to “drill down” into a report to view detail in large data sets. From a distribution perspective, reports and analytics can be set up to be sent to individuals or groups of people on a routine basis, or data can be structured for ad hoc advanced manipulation by a handful of superusers with a deeper level of analytics skill. Most organizations find that a hybrid approach of routine reporting being “pushed” to users combined with advanced reporting being “pulled” by superusers meets most stakeholders’ needs.

To Warehouse or to Mart

SOMs have two choices to make in determining the overarching scope of the BI effort: a full-scale data warehouse or an academic mission- or department-specific data mart (or series of marts). A data warehouse, as illustrated on the previous page, integrates information from multiple information systems. Data marts, however, are specific to one subject area or system – for example, finance, research, or grants management – and are often smaller in size and scope than a warehouse.

A mart strategy is very consistent with an SOM environment that tends to have data, systems, and budgets specific to missions, departments, or institutes. As data marts are developed and mature, data can be made consistent between marts so that information may be integrated across the SOM. For example, the definition of a “student” or a “grant” would need to be made consistent so that this information can be shared across marts. In a warehouse, these definitions have to be standardized as part of the initial ETL process to ensure consistency. By applying a consistent data architecture, an SOM can begin BI efforts on a smaller scale with marts and move toward a larger data schema in the long term. While data marts may offer some value early, if they are built without an eye to future integration with other data marts, it can mean constantly reorganizing data mart solutions and, ultimately, higher costs.

On the other hand, a well-designed and comprehensive data warehouse provides a solution that is more responsive to the needs of the enterprise as a whole. It can be capitalized in a single effort and have a shorter total implementation timeline. On the downside, a warehouse requires significantly more capital and management up front. As a result, most data warehouses are developed in phases.

Determining Scope

Determining the right scope of the BI initiative will depend on your SOM’s budget, resource availability, and the status of source information systems. A conservative strategy would defer a comprehensive, organization wide data warehouse that aims to integrate all sources of data in favor of addressing the key requirements of the BI program (e.g., consolidating and standardizing financial information from disparate university, practice plan, and other reporting systems into a unified, all-funds statement for clinical departments) in the short term. This approach could then be expanded over time to include additional data sources, architecture development, additional technology, and infrastructure to build a broader warehouse. If a comprehensive warehouse strategy is required to meet the immediate needs of stakeholders, the SOM should ensure that it has adequate data from source systems to meet these needs. Too often, organizations perceive BI as enhancing the availability of data, when, in actuality, BI will not function properly if data doesn’t already exist.

An SOM might be able to leverage an existing BI effort from its university, an affiliated health system, or a faculty practice plan. If this is possible, key questions to ask include:

- Are the SOM’s BI needs aligned with those of the organization hosting the warehouse?

- Is the technology scalable to include data from SOM systems?

- What resources will the SOM need to provide for the effort to be successful? Are those resources readily available?

- How will the BI effort be governed? Will the SOM have adequate influence over this process to ensure that its needs are met?

Evaluating Systems Options

There are essentially three types of vendor options for BI. Loosely, these can be grouped as follows:

- Healthcare Vendor – Specific BI or Reporting Capabilities – Most of the major healthcare enterprise system vendors (e.g., Allscripts, Epic Systems Corporation, Cerner Corporation, McKesson Corporation, MEDITECH) have developed reporting tools that cross their various system components or modules to enable organizations to complete complex analyses. The benefit of these systems is that they are typically well integrated with the source systems. The drawback is that it may not be easy to integrate data from other SOM systems without extensive programming. This approach may be the most appropriate if the SOM and health system are tightly integrated and if the BI environment of the health system can be extended to encompass SOM data. This may also be the simplest solution for programs requiring very little integration of data across source systems.

- Healthcare-Targeted, Vendor-Independent BI Tools – Vendors such as MedeAnalytics, Inc., Streamline Health, Inc., Healthcare DataWorks, Inc., and others have developed BI tools to specifically solve healthcare problems. Most of the products developed to date for healthcare are focused at the health system level (such as toward accountable care organizations, revenue cycle, and health reform), not the SOM level. Since these products are not specifically designed for certain source system vendors, they may provide greater flexibility in integrating a variety of source systems.

- Industry-Independent BI Tools – BI has been well established in a variety of industries for over a decade. Vendors such as IBM, SAP, Microsoft, Tableau Software, Dimensional Insight, Information Builders, and others have deep BI experience across industries and have recently developed healthcare-oriented products. Again, these tools are typically focused on “big data” problems such as population management rather than on addressing SOM management issues. However, because these tools are industry independent, they are often well suited to manipulating information within a wide variety of systems and organizations (university, SOM, health system, health plan, etc.).

Additionally, an SOM may wish to evaluate the components of the BI initiative separately and select a “best of breed” approach to warehousing, ETL, reporting, viewers, etc. This may provide stronger tools for each area but may also create additional technical requirements and potentially costs if the solutions are not bundled together.

The Bottom Line

A BI effort for SOMs can bring together data from diverse, siloed systems to create useful information for the planning and management of an integrated enterprise. Difficult choices are required, however, including whether to build a new system, modify an existing system, or cobble together a number of systems as best you can. Key issues in making these decisions include organizational capabilities, the status of existing systems, the availability of capital, and the requirements of your organizational strategy. While complex and frequently confusing, it should be understood that BI will be critical for the success of the SOM going forward.