General Hospital is continuing to grow its employed physician network by not only recruiting physicians to join its established practices but also by acquiring independent practices. The hospital’s leadership has spent time identifying the drivers of its physician network and developing a comprehensive strategic plan to meet community needs, address the competitive environment, and comply with current and anticipated payer requirements. An executive team with appropriate ambulatory care experience has been recruited, including a chief medical officer that the physicians seem to trust and respect. But General Hospital is encountering operational challenges with its acquired practices. These challenges include high rates of turnover among clinical and office support staff, poor adoption of the electronic medical record (EMR), and inconsistent and inefficient work flows.

The acquisition of independent practices by hospitals as a strategy for physician network growth is becoming increasingly mainstream. As a result, various recommendations and tools have become prevalent in terms of evaluating which practices to acquire and how to ultimately complete the transaction; common practice is for an organization to allocate most of its effort to this acquisition planning. But once the documents are signed, it is important to understand how to introduce and integrate these practices into the physician network and the overall health system; therefore, best practice is to increase the overall level of effort so that proper attention can be paid to post-transaction planning. In reality, acquiring the practices is the easy part; ensuring optimal and consistent performance and the subsequent achievement of strategic goals are the hard parts.

All too often, physicians view a hospital employment arrangement as little more than a change in the source of their paychecks. They still intend to operate as independent providers on a day-to-day basis with a certain sense of autonomy about what happens within the walls of their practices. The reality is that all practices must be comprehensively assessed for operational effectiveness and that changes are inevitable; physicians must give up some control once they become part of the larger enterprise and allow these changes to occur. In the short term, physicians may be resistant and frustrated, but over time, they will recognize and appreciate the improvements that alleviate the administrative burdens of running a private practice.

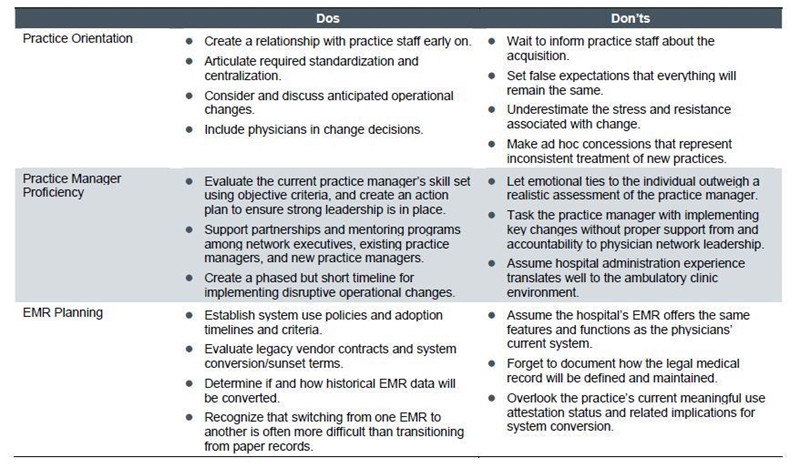

In our experience, there are three critical components in effectively on-boarding an acquired practice: practice orientation, practice manager proficiency, and EMR planning.

- Practice Orientation – Practice acquisition can be a worrisome proposition for clinic staff, who may wonder if they have a future in the larger physician network. Too often, physicians try to protect staff and keep them in the dark until the last minute, triggering anxiety, fear, and even turnover. Staff are less willing to learn and adhere to standardized processes as defined by the network if they feel threatened and defensive. To avoid this, hold onsite meetings with practice staff early and often. Answer their questions, engage them in the process, and support the cultural transition. Do not rely solely on manuals, policy and procedure documents, and other written communications and reference materials. Require the attendance of physicians and staff and block off schedules for 4 to 8 hours to allow for a dedicated focus on the on-boarding and relationship-building process.

- Practice Manager Proficiency – Don’t underestimate the value of having a strong practice manager in place throughout the acquisition process. While it may be tempting to acquire the clinic first and review staffing competencies later, the legacy practice manager may not have the skills necessary to transition the practice into the network. The right person for the job has sophisticated management skills combined with a track record of clinic management (rather than hospital administration) experience. With the help of the executive team as well as network peers, the practice manager should lead efforts to assess the operational processes and performance of the practice in comparison to the expectations and standards set forth by the network. Each individual and job function needs to be evaluated so that adjustments – which may include outplacement to other areas of the health system, layoffs, or recruitment – are done quickly and in a transparent fashion. The manager should be willing and able to execute the necessary changes.

- EMR Planning – The needs and steps to transition a practice from its legacy billing system to that of the hospital’s physician network are typically straightforward and well understood. As it is becoming more common for independent physician practices to have already implemented an EMR, the topic of system conversion to the hospital’s ambulatory EMR becomes important, although somewhat new, territory. Policies should be established for how long the new physicians have to adopt the EMR and what adoption really means. Also, guidelines are needed with regard to data conversion from the legacy system – all, none, or some? Manually or electronically? By whom and for how much? It is vital that all members of the physician network ultimately work from the same platform, and the process for reaching that goal cannot be an afterthought.

The details outlined in the initial term sheet and, ultimately, the final contract don’t address the cultural shift faced by private practices or the need for potentially swift and significant operational changes. But the goals of the employed physician network will never be fully realized unless the hospital sets accurate expectations from the start, consistently follows through to ensure operational effectiveness, and commits to having the right people in place to lead these efforts.