The Trend: Greater Investment

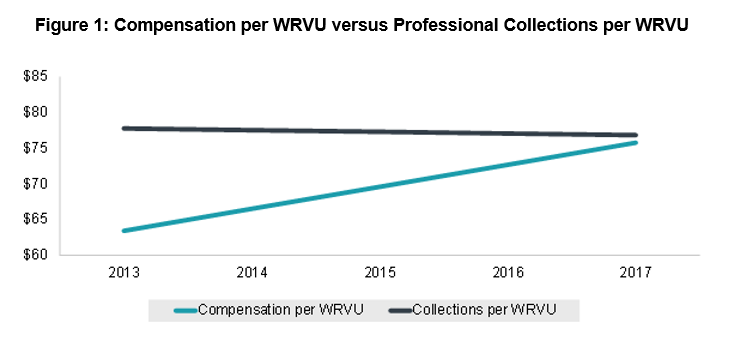

Pediatric administrators across the country are confronting the reality of increasing provider costs and decreasing associated professional revenues. This has prompted difficult conversations about who will fund the resulting deficits and how the underlying causes of these trends can be mitigated. This is underscored by results from ECG’s Pediatric Subspecialty Physician Compensation Survey, which recently reported a steady five-year trend wherein professional collections per WRVU have remained stagnant, while compensation per WRVU has increased to the point that it is nearly equal to the collections metric. As the WRVU has become the barometer for measuring both provider productivity and payment for professional services, the trend of flat collections and rising compensation per WRVU is an increasingly clear and a stark reminder of the need for additional financing of pediatric providers in order to maintain benchmark salaries. For larger pediatric groups, additional funding requirements may be in the millions and growing.

As shown in figure 1 below, the median compensation per WRVU increased from $63.42 to $75.77 from 2013 to 2017 (+19.5% over that period), while the median net professional collections per WRVU decreased from $77.77 to $76.83 (-1.2%).

What Is Driving This?

On the revenue side of the equation, the evolution of the pediatric payer mix is nothing new. CHIP enrollment grew by 17% from 2014 to 2017, countering efforts by providers to improve commercial insurance payment rates. This has collectively driven stagnant or diminishing collections per WRVU across pediatric specialties.

Conversely, compensation for pediatric subspecialists has continued to increase. In the past, rising compensation tended to be attributed to demand outpacing supply, as pediatric programs reported shortages in key subspecialties, extended wait times for appointments, and long times to fill vacant positions.

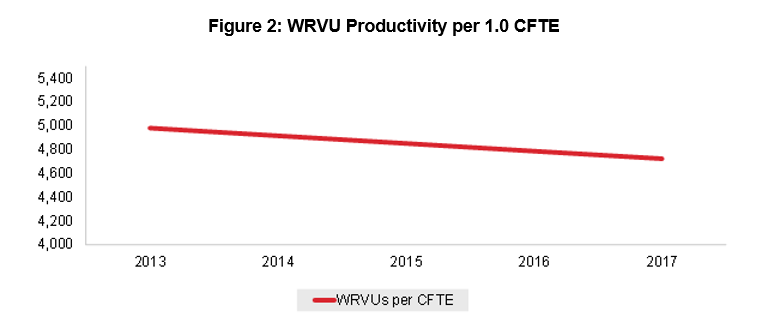

Today, the supply/demand dynamic that is driving compensation is more nuanced. Major factors include shifting work expectations for physicians and the broad introduction of advanced practice practitioners (APPs). Providers are requiring more favorable clinical schedules and protected academic time while expecting financial incentives for “incremental” responsibilities like call coverage, quality committee membership, and the oversight of student learners. What constitutes a 1.0 clinical FTE (CFTE) for many shift-based specialties has steadily decreased over the past decade. The evolution of how physicians work and how their time is recognized has heightened the need for APPs, who increasingly supplement provider capacity by working autonomously by their physician counterparts’ sides.

The resulting increase in the required investment in physicians made by health systems has led organizations across the country to think critically about how their providers are compensated and incentivized and the level and mix of their staffing models across sites of service.

As shown in figure 2, WRVUs per 1.0 physician CFTE have decreased by 1.5% annually since 2013, according to ECG’s Pediatric Subspecialty Physician Compensation Survey .

Four Impactful Responses to this Trend

Pediatric programs are performing self-evaluations in four main areas in order to contain provider costs and maximize investments.

1. Optimize Provider Deployment

Clearly Define CFTEs

Every pediatric employer should have clear definitions for what constitutes a CFTE for each department and service line. Even further, they should estimate the clinical deployment by inpatient, outpatient, surgical time, outreach time, etc. for the upcoming period and track provider effort against those estimates. If a provider is expected to spend 0.4 CFTEs in an ambulatory setting, there should be guidelines equating that deployment to a set number of “blocks” worked and patient visits completed based on the physician’s scheduling templates. The core metric for the inpatient setting is shifts covered, and for surgical time, it is OR blocks. Actual physician effort will deviate from these expectations for a variety of reasons, but the tracking of deviations will help explain lags in provider production, OR utilization, and patient access, among other key metrics. However, these expectations are often poorly defined, communicated, and tracked.

Manage Your Medical Direction Investment

Clinical leadership is one of the most important services a hospital can buy from its physician partners. However, too often, directorship roles or CFTEs are subject to institutional inertia and left to roll over each fiscal year with little discrimination or structural oversight. Forward-thinking children’s hospitals are now establishing a finite grouping of administrative investment for physicians and following an annual process whereby the time allocated to certain roles or initiatives is adjusted to align with the strategic, operational, or quality initiatives of the organization. This drives mutual accountability and helps restrict the creep of administrative investment, especially when the prior impetus for certain roles has resolved and that investment can be better allocated elsewhere.

Define and Manage Academic Investment

A high proportion of pediatric subspecialty providers work in academic medical centers, and they constantly balance clinical and academic demands (research and teaching). Institutional financing for academic activity has long been flat or declining. As clinical time is more clearly defined, the same must happen for academic time.

2. Construct the Right Care Teams

One question every pediatric organization is grappling with right now is determining the optimal mix of providers, nurses, and support staff in each clinical setting. While ratios can vary dramatically, the overarching direction organizations have taken is to ensure all providers are empowered to work at the peak of their licensure. This is a complex equation with many variables, but it requires scheduling templates and practices with the requisite mix of rules and adaptability. Each group must determine if APPs can be used to supplement their physician workforce. In many service lines, APPs see low-complexity patients, freeing up physicians to see the highly complex cases that represent the best use of their time and training. However, to achieve their full capacity, APPs require similar scheduling structure, support staff, and facility space as their physician counterparts.

3. Build the Right Compensation Incentives

For employed physicians, compensation plans have evolved past basic production-based incentives to recognize individual- and team-based measures pertaining to quality, cost containment, patient satisfaction, operational efficiency, and medical staff citizenship such as participation in committees that drive care model innovation. The way providers are compensated reflects the organization’s culture and begets it in the future, so it is critical that providers understand how they are compensated and feel they can influence the metrics for which they are incentivized. Contemporary plans should encourage open communication and team-based medicine, and the incentives selected should align provider behaviors with the strategic goals of the organization.

4. Reevaluate Organizational Funds Flows

While many hospital-based providers and APPs are employed directly by the hospital, for many children’s hospitals, providers may be employed by a school of medicine or outside medical groups. In a high-trust, high-functioning services arrangement, a degree of transparency is built into operational and financial measures that ensures the providers are delivering the exact services the hospital believes it is purchasing. Beyond this, there are mechanisms in the arrangement terms, governance/organizational structure, and reporting infrastructure that ensure strategic goals are aligned and reinforced through financial incentives.

Though pediatric hospitals often cannot influence the compensation plan for individual physicians, the organization can increase transparency by renegotiating contract terms such that physicians are held accountable to their operating budget and productivity targets.

What to Expect Moving Forward

The evolution of the pediatric payer mix and the push by commercial payers for more competitive rates will continue to tighten margins. Moreover, physician work expectations will continue to evolve, and the use of APPs will expand. As a result, pediatric hospitals and programs will need to proactively evaluate the areas identified above in order to insure financial viability of the provider enterprise.